This article is a collaboration between ������Ƶ and:

Shooting up Opana landed 38-year-old James Gibbons in the hospital -- but not because of an overdose.

The Shawnee, Okla., resident developed permanent heart, lung, and kidney damage after the oxymorphone drug caused a clotting disorder that cut off vital blood supply to those organs.

Now, he's awaiting valve replacement surgery, and he'll be on dialysis for the rest of his life unless he gets a kidney transplant.

Action Points

- Intravenous abuse of orally-formulated extended-release oxymorphone (OPANA ER) is increasingly reported as a cause of a thrombotic disorder resembling TTP or other thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).

- Because large needles are needed to inject OPANA ER, infectious agents are easily introduced into the bloodstream.

"He's kicking himself in the butt for doing this to himself," said his aunt, Jane Childers, who drove Gibbons to the hospital after he showed up at her house weak, dehydrated, and jaundiced. "I knew when I saw the chalky yellow color of his skin that we were in trouble."

The , known as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), in October 2012, although researchers are now suggesting the condition more closely resembles a more general clotting disorder, thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA).

The CDC soon followed with a that described 15 cases of "TTP-like illness" in Tennessee, urging healthcare providers to ask patients about injection drug use if they saw similar cases.

But Childers said Gibbons' illness went undiagnosed for weeks by doctors at OU Medical Center in Oklahoma City, and she's worried that not all healthcare providers are aware of the potential side effect of abuse.

Not Really Abuse-Deterrent?

The blood-clotting disorder has been limited to the abuse-deterrent formulation of Opana, which drugmaker Endo Pharmaceuticals put on the market in early 2012.

The new version of the drug was intended to be harder to abuse. An outer coating was supposed to make it too hard to crush so that it couldn't be snorted, and it was supposed to turn into a thick gooey gel if it was dissolved or melted. That way it couldn't be drawn up into a syringe and injected.

Those determined to abuse the drug couldn't foil the anti-snorting mechanism, but they found a way to melt it down and inject it, with the help of larger gauge needles that could still channel the thicker substance into veins.

Other opioids have adopted similar abuse-deterrent technologies, particularly OxyContin, which has been implicated as a major contributor to the opioid-abuse epidemic in the U.S. When drugmaker Purdue Pharma put the new version on the market in 2010, the FDA banished OxyContin generics, citing concerns that the old version was easily abused.

But Endo Pharmaceuticals did not win abuse-deterrent labeling from the FDA. Although the agency's decision wasn't clear at the time, some experts said they may have made the right call about problems with reformulated Opana's abuse-deterrent technology.

, chief medical officer of the addiction recovery program Phoenix House, said abuse of reformulated OxyContin is rare, potentially because both its anti-snorting and anti-injection technology work.

"I've heard that making Opana harder to crush led some folks to shift from snorting to injecting it because the [abuse-deterrent formulation] was effective for stopping snorting but easy to defeat for injecting," Kolodny said.

Opana Versus OxyContin

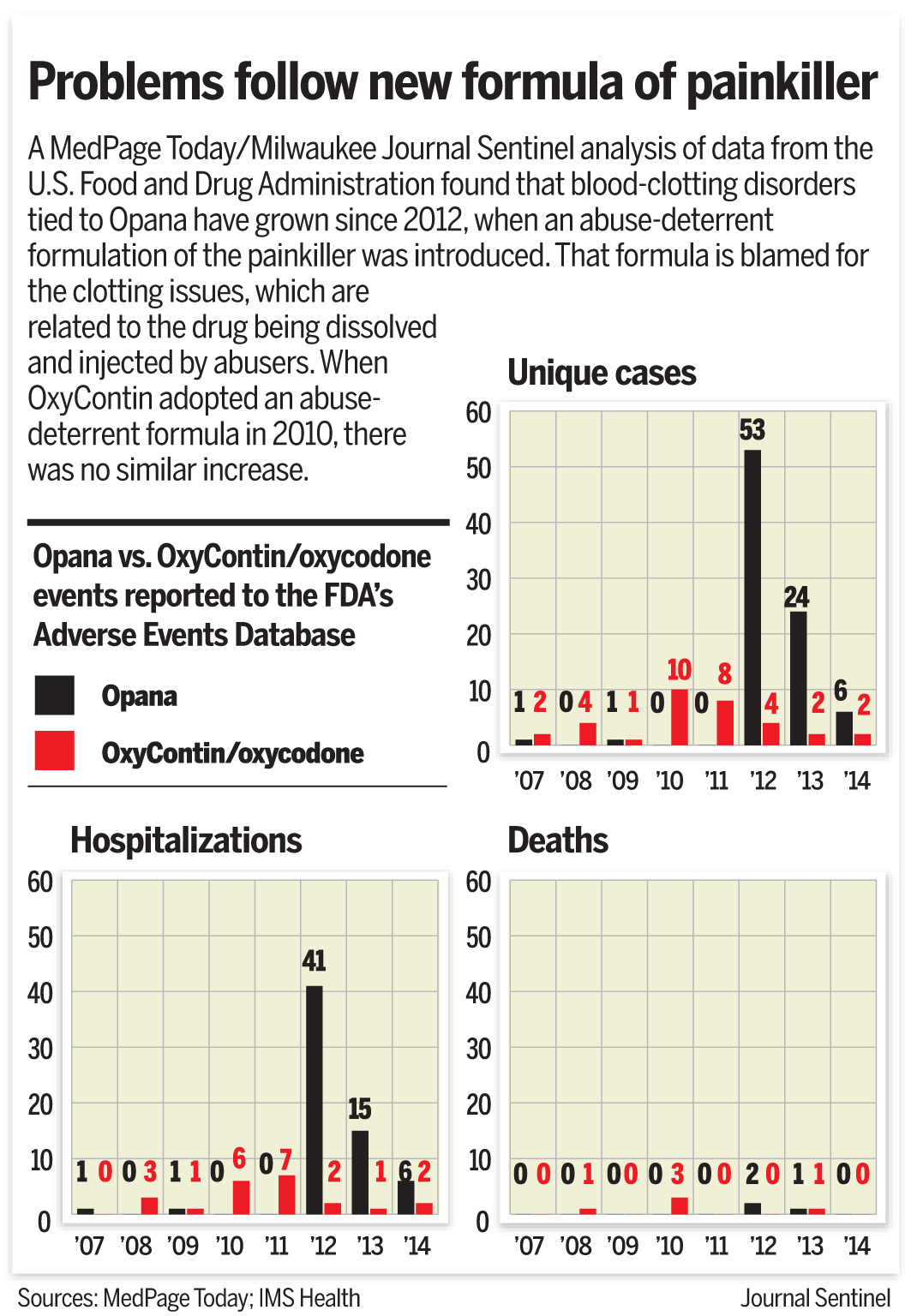

A ������Ƶ/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel analysis of FDA adverse events reporting system (FAERS) data found that blood-clotting disorders are a bigger problem for Opana than OxyContin.

In the 4 years prior to reformulation, there were only two cases of blood clotting disorders with Opana as the primary suspect. But in 2012, there were 53 cases -- accounting for some 5% of all adverse event reports where Opana was the primary suspect.

There were 24 cases in 2013 and six cases in 2014 (although data were not yet complete for this year), accounting for 18% and 10% of all Opana adverse event reports, respectively. Cases can take years to be reported to the FDA's system, meaning the number of Opana reports overall would likely increase. Although the data are known to be incomplete for a multitude of reasons, it is still the only public indicator of problems with drugs that are currently on the market.

By comparison, there were seven cases of blood clotting disorder in the 3 years prior to OxyContin formulation, and the numbers didn't change much thereafter. The analysis showed 10 cases in 2010, followed by eight cases in 2011, and four in 2012, dropping off to two each year thereafter.

Those reports made up 1% or less of all adverse event reports with OxyContin for each year.

Endo added a warning about thrombotic microangiopathy to the drug's label in April 2014.

Company spokesperson Heather Zoumas Lubeski said in an email to ������Ƶ that the company is actively researching the cause of the blood clotting problems, but that research "is still in the preliminary stages" and company scientists would not be able to comment.

She added that Endo is "unaware of any reports that this rare condition has occurred in any individuals who use the product appropriately."

Cause Unclear

It's not immediately clear what it is about abuse-deterrent Opana that is causing the blood clotting disorder. The authors of the 2013 CDC case report noted that the inactive ingredients not found in the original version of Opana include polyethylene oxide (PEO) and polyethylene glycol (PEG).

But reformulated OxyContin also contains PEO and has not been tied to the same problems, they said.

The other possibility is that OxyContin's anti-injection mechanisms can't be foiled, while Opana's can. Although Opana is still thick when melted down, abusers appear to be able to inject it via large-gauge needles.

Indeed, officials in Indiana and at the CDC have using larger needles. There have been 136 cases of HIV since November 2014, mostly in injection drug users.

"That is making the sharing of needles an even higher-risk activity, because you're being inoculated with higher amounts of HIV virus," Indiana state health commissioner , told reporters during a press briefing last month.

The larger needles make patients more susceptible to other kinds of infections as well. Some patients have also contracted infections of the lung and heart because the larger gauge needles are introducing more bacteria to the blood stream, as was the case for James Gibbons in Oklahoma. He needs valve replacement surgery to treat the damage done by endocarditis.

Endo also added a warning about HIV transmission to Opana's label in 2014. It's in the same paragraph as the language on blood clotting disorder.

Secondary Effects

The FDA data may signal a drop off in cases of blood clotting disorders, possibly as users become aware of the potential complication and avoid abusing it.

Health officials in Tennessee and Kentucky, which reported cases in the 2013 CDC report, as well as those in Indiana, told ������Ƶ they did not have updated data on blood clotting disorders associated with Opana.

Health officials in Oklahoma -- where Gibbons was diagnosed and treated -- said they did not have data on such cases either.

Physicians on the front lines of treating Opana-related blood disorders have reported several cases in the literature. In addition to the 2013 CDC report, a in the American Journal of Kidney Disease listed three cases, and a in the American Journal of Hematology detailed 15 cases.

, of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., was the lead author of the hematology journal report. He said his team was consulted when the mysterious rash of blood clotting problems started popping up.

Initially they treated the patients with plasmapheresis, but soon discovered that wasn't necessary since the illness wasn't true TTP. They confirmed their findings by looking for the ADAMTS13 antibody, which only turns up if TTP is to blame.

Patients who screened clear of the antibody were treated with best supportive care and did well, Miller said.

His advice to physicians who see TTP-like illness in injection drug users: "If you presume someone has TTP, err on the side of caution and treat it [with plasmapheresis] first, and check the ADAMTS13 later. Then back off therapy."

, of East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, Tenn., published her experience with Opana and blood clotting disorder in .

Kapila told ������Ƶ that her hospital has been treating Opana-induced blood clotting disorders for years now, and they are starting to see lingering complications.

For instance, many of the patients who had to go on dialysis now come to the emergency department overloaded with fluids. Physicians couldn't give them a regular access port for dialysis, because that would give them easy access to continue abusing drugs.

Instead, these patients were candidates for peritoneal dialysis. But the fact that they're young injection-drug users makes for a noncompliant population, Kapila said.

"They come in super fluid overloaded," Kapila told ������Ƶ. "So we're dealing with these sequelae from the initial treatment now."

While some physicians in some areas of the country have a lot of experience with Opana-related blood disorders and are already seeing secondary effects, others haven't dealt with the problem as often -- as was the case for Jane Childers' nephew.

"I'm alarmed at the number of people in the Shawnee area who are melting down and shooting these Opanas," Childers told ������Ƶ. "I understand there have been warnings, and people aren't supposed to abuse these drugs. But it's happening. There will be more life-threatening illnesses and deaths."

Coulter Jones contributed data reporting to this story.

Disclosures

Miller and co-authors disclosed no relevant relationships with industry.

Kapila and co-authors disclosed no relevant relationships with industry.

Primary Source

American Journal of Hematology

Miller PJ, et al "Successful treatment of intravenously abused oral Opana ER-induced thrombotic microangiopathy without plasma exchange" Am J Hematol 2014; DOI: 10.1002/ajh.23720.